by Andy Chen | Jun 15, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff, Torts

Today’s post is going to be another short one. In it, I’m going to go over the statute of limitations for a wrongful death lawsuit in California state court. As a reminder, a “statute of limitations” is the time period within which a plaintiff wanting to file a civil lawsuit (e.g. seeking money) must do it in. If the plaintiff waits too long (e.g. even by one day), they will lose their lawsuit simply because they waited too long. The topic of wrongful death litigation can get complicated when you look at questions such as (1) who is an acceptable plaintiff in a wrongful death suit?, and (2) what damages can be recovered in a wrongful death suit? I’ll go over these questions in future posts, but for today’s post, I’m going to look at just the time element involved, namely the statute of limitations the plaintiff has to file their civil suit within. In California, the answer is two years. Under Section 335.1 of California’s Code of Civil Procedure, a plaintiff in a wrongful death lawsuit must file that suit within two years of the date the death in question occurs. Section 335.1 itself says the following: “Within two years: An action for assault, battery, or injury to, or for the death of, an individual caused by the wrongful act or neglect of another.” Two years, however, is the general rule of thumb to remember. However, as with many things in law, exceptions can exist which may make the actual statute of limitations in your case shorter than two years. If that applies in your situation, you obviously...

by Andy Chen | Jun 13, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

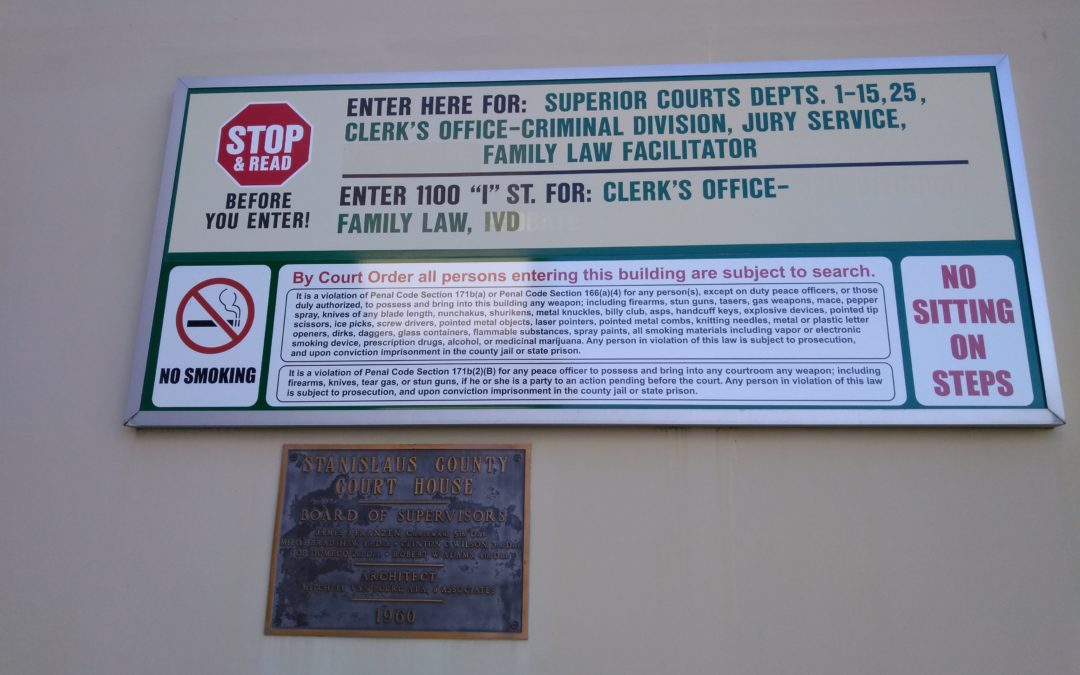

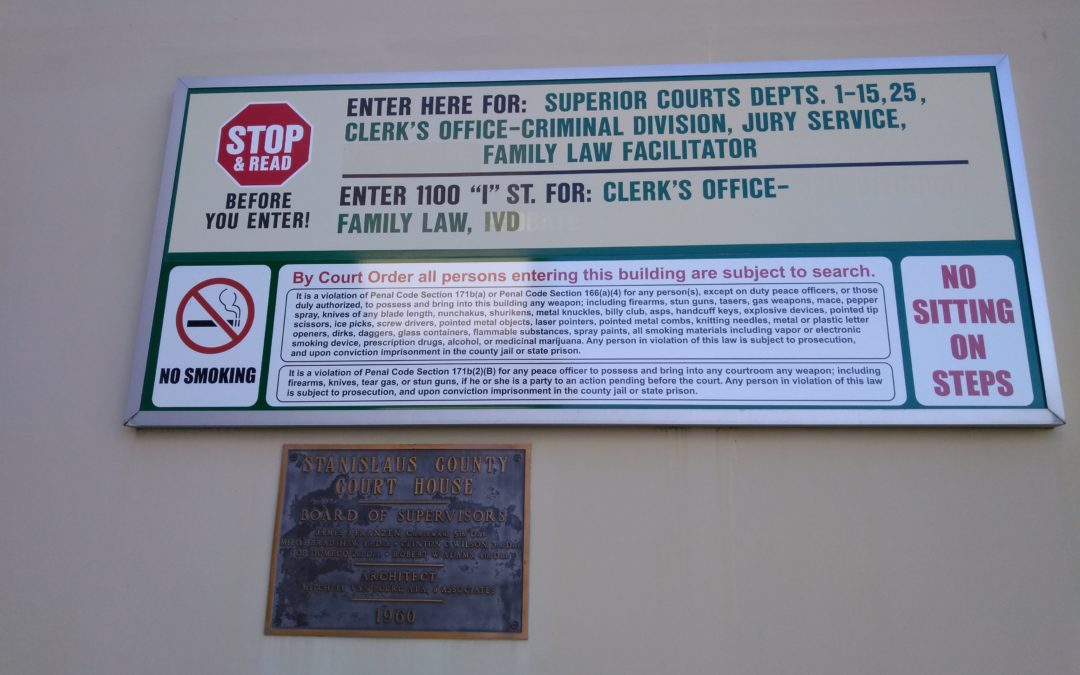

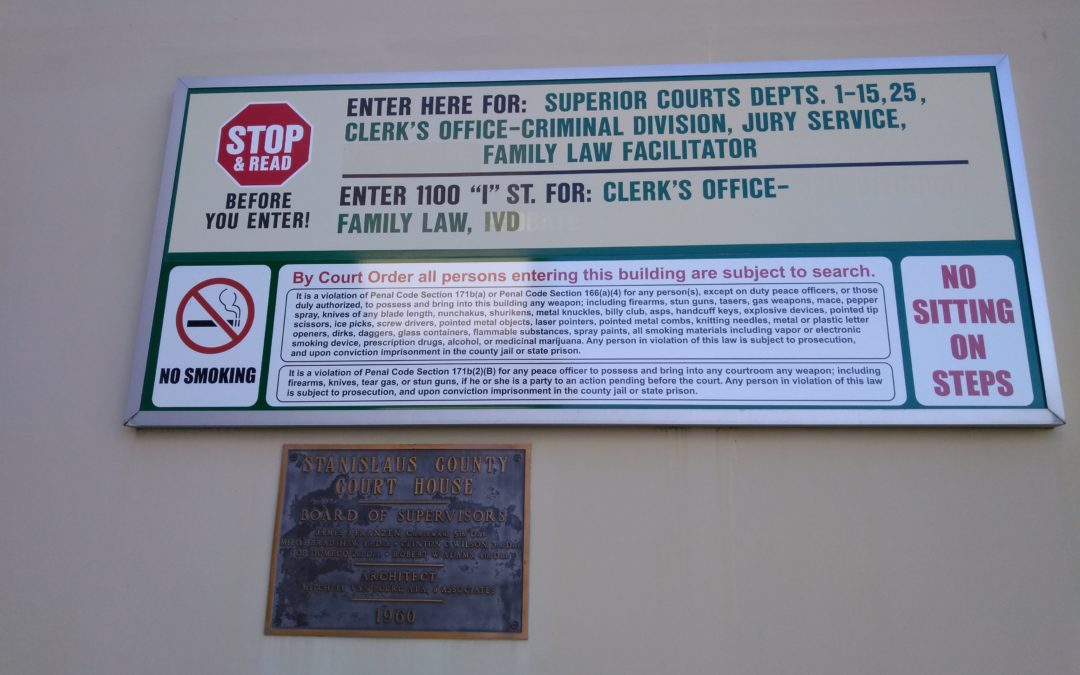

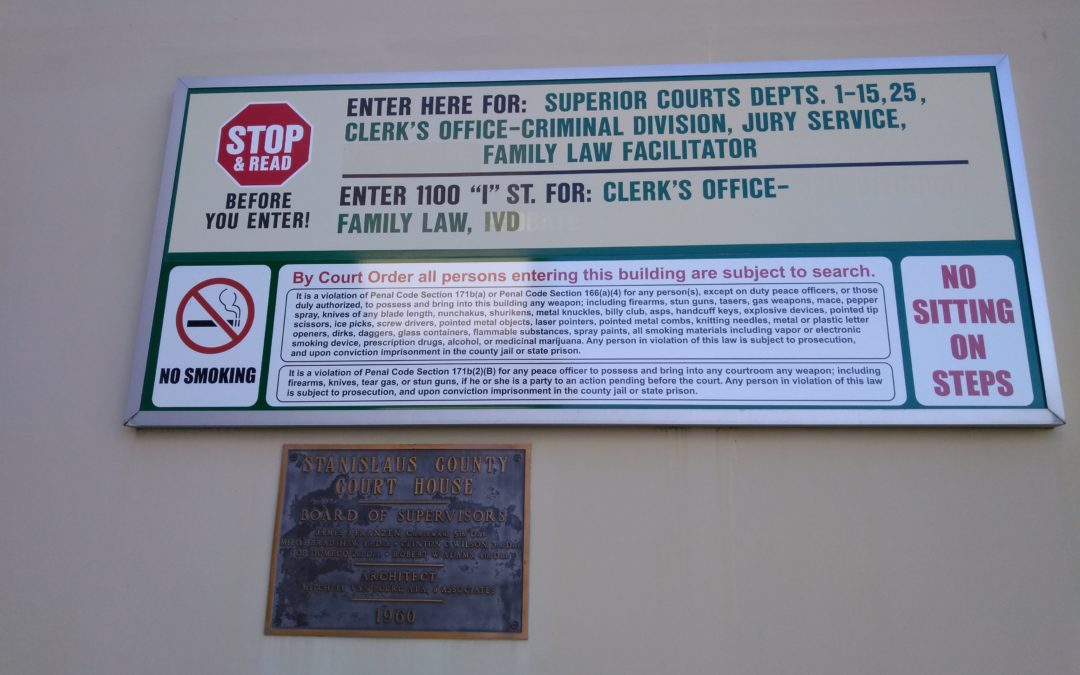

I would have thought it common sense that you shouldn’t bring a weapon to court unless you’re a law enforcement officer, using the weapon as evidence in a case, etc. However, in case it isn’t common sense, there’s this sign at the entrance to the Criminal and Family courthouse in Modesto, California. If you look under the red wording that says “By Court Order, all persons entering this building are subject to search”, you’ll see that it’s a crime to bring any of a whole littany of weapons in to the courthouse, including but not limited to, firearms, stun guns, tasers, gas weapons, and mace. The statutory authority for that is California Penal Code section 171b which, in a nutshell, outlaws the bringing and possessing of weapons in to a state or local public building. Section 171b also lists out a whole bunch of exceptions to this prohibition, such as law enforcement officers, people using the weapon as evidence in a case, and people who have been specifically granted permission to bring the weapon in. The prohibition does, however, remain in effect (i.e. it’s an exception to the exception to the prohibition) as to those persons who are parties to a case. For instance, a law enforcement officer can carry their firearm if they are on-duty (e.g. a sheriff’s deputy working as a baliff at the courthouse), but if they are showing up for a child custody hearing in their own divorce, then they can’t. You can read over the entirety of Section 171b at your leisure, but I want to point out the section’s definition of a “state...

by Andy Chen | Jun 2, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff, Torts

For a change of pace, I’m going to do a short post. (I can hear all of you now collectively going “Finally!”) The topic of today’s post is the statute of limitations for a negligence action in California. As a reminder, a statute of limitations is the time period within which a plaintiff has to file their civil suit seeking redress from the defendant. As a general rule of thumb, this proverbial clock starts to run when the last criteria that needs to be met in order to prove the lawsuit occurs. Phrased another way, if you need to prove 5 criteria in order to win your lawsuit, your statute of limitations clock doesn’t start to run until the 5th and final criteria occurs. In California, the negligence statute of limitations is 2 years under Section 335.1 of California’s Code of Civil Procedure. Section 335.1 states “Within two years: An action for assault, battery, or injury to, or for the death of, an individual caused by the wrongful act or neglect of another.” An example where this might apply would be a car accident where the plaintiff suffered injuries of some kind to their body. There are many exceptions to this two-year rule, however. For example, if your case involves asbestos exposure of some kind, the statute of limitations could be as short as one year under Section 340.2 of California’s Code of Civil Procedure. If you have a situation involving negligence in California, the best way to know what statute of limitations applies to you is to find a lawyer with whom you can discuss the details of...

by Andy Chen | Apr 29, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

In prior posts, I’ve gone over issues such as the presentation requirement when an attorney and client sign a fee agreement. On my Youtube channel, I’ve also gone over topics such as what a California contingency fee agreement has to have. In this post, I’m going to go over California’s requirements for a fee agreement when the agreement is negotiated in a language other than English. The relevant California statute is going to be section 1632 of the California Civil Code. If you read section 1632, you’ll quickly notice that it is not specific to attorney fee agreements, but discusses more broadly the question of when a written contract needs to be provided in a language that isn’t English. The relevant portion of section 1632 that applies to fee agreements between clients and attorneys is sub-section (b)(6), which provides: “Any person engaged in a trade or business who negotiates primarily in Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, or Korean, orally or in writing, in the course of entering into any of the following, shall deliver to the other party to the contract or agreement and prior to the execution thereof, a translation of the contract or agreement in the language in which the contract or agreement was negotiated, that includes a translation of every term and condition in that contract or agreement: (6) A contract or agreement, containing a statement of fees or charges, entered into for the purpose of obtaining legal services, when the person who is engaged in business is currently licensed to practice law pursuant to Chapter 4 (commencing with Section 6000) of Division 3 of the Business...

by Andy Chen | Apr 26, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

If you didn’t know, I have a Youtube channel in addition to this blog that I, more or less, regularly post to. A while ago, I put out a video on the Youtube channel about contingency fee agreements used by attorneys in California. Here it is: Actually, to be technically correct, I put out two videos. The one I embedded above talks about contingency fee agreements in California cases generally (i.e. all cases except family law). The other video (linked here) talks about contingency fee agreements in family law cases because the question of ‘Can I use a contingency fee agreement in a family law case?’ often comes up. For background, a “fee agreement” is the contract you sign when you hire an attorney. These agreements are, of course, not specific to California. If you’re going to hire a lawyer in another US state, chances are that lawyer will want a fee agreement of some sort signed also. California, though, has numerous rules that fee agreements have to satisfy. I went over some of those rules in my videos (e.g. required contents of a fee agreement). In this post, though, I’m going to go over the rules relating to presentation. What “presentation” refers to is that a client needs to be given a copy of the fee agreement after it has been signed. Personally, I would have thought it blatantly obvious that a client needs to get a copy of their signed fee agreement, but it apparently isn’t that obvious because it’s addressed not only once, but twice in California’s statutes. The first is in section 6147(a) of the...

by Andy Chen | Apr 20, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

When it comes to the law and court cases, it is extremely common to have to serve documents by mail. You can serve documents in person as well, of course, but that can be inconvenient or impractical given the need to coordinate schedules, locations, etc. It’s obviously much more convenient to be able to serve legal documents by simply dropping it in the US Mail. If you subscribe to my Youtube channel, you’ll know that I have a video on how to fill in California Judicial Council form FL-335 (available here), or Proof of Service by Mail for California Family Law cases. Here’s the video: There is an equivalent proof of service by mail form in California civil court (i.e. the form POS-030, which is available here). I don’t have a video on the POS-030, but the concept is virtually identical to the FL-335. The keen-eyed among you, though, will have realized a flaw in the concept of a proof of service by mail: “Just because I drop it in the mail, doesn’t mean it gets there. What happens if it gets lost in the mail?” There are two answers to this excellent question. First, the US Mail does occasionally lose items. Moving mail in the scale that the US Postal Service does involves a ton of human labor and machines so mistakes and accidents do happen. In my experience, though, lost mail happens far less often than people claim. In the vast majority — I would say 95% of the time — of instances, legal documents that are served by mail do arrive as they are supposed to....