by Andy Chen | Jun 24, 2021 | California, Feel good series, Statutes... and stuff

This past week, I came across several memes on Facebook about what you’re supposed to do in California if you encounter a dog or other animal locked inside a vehicle with the windows up. The concern, of course, is that the interior of the car will overheat on a summer day and the animal will die. Being the legal research nerd that I am, I took it upon myself to look up the relevant and bore — er, I mean, share — that law with all of you. It’s also an opportunity for me to share a lot of the dog photos I’ve accumulated over the years. Anyway, there are two questions I’ll answer: What California law prohibits leaving a dog or other animal in a hot car? What California laws allow a bystander who sees a dog locked in a hot car to break the window of that car to rescue that dog or animal? #1: What law prohibits leaving a dog in a hot car? The relevant California law here is Section 597.7 of California’s Penal Code. Section 597.7 has a lot of subsections to it so I would encourage you to read the actual text of the statute if you have a situation that involves an animal having been left in a hot vehicle. As I’ve mentioned before, my posts are ultimately just my paraphrasing of the relevant law. I’ve included links in this post and in all my other posts to the relevant code sections in California should you want to do your own research. Anyway, the subsection that addresses the leaving of animals in...

by Andy Chen | Jun 21, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

In this post, I’m going to talk about California Living Trusts and specifically a very common situation that I encounter relating to trustees and beneficiaries. The basic scenario is something like this: Elderly parents who made a living trust years ago, but are now too infirm to really handle things themselves so someone else is serving as trustee of the Living Trust. That trustee is a lay person and, basically, is doing something incorrectly. This incorrect thing that the trustee is doing can vary greatly. On the one hand, it might be that the trustee is doing everything properly, but they just haven’t filled out the right forms simply because they didn’t know that they had to do that. Correcting the problem (e.g. filling out the right forms) is easy. On the other hand, it’s also extremely common for the trustee to knowingly and purposely do something incorrectly. In other words, the fact that the trustee is not a lawyer or has never been a trustee before is not an excuse. They should have known regardless that what they were doing was wrong. A very common example of this is taking money from the trust for the trustee’s own personal use. The beneficiaries to the trust suspect that the trustee is doing something improper because the trustee refuses to talk to them, won’t let them see the trust document itself, etc., but don’t know for sure because the trustee is being so tight-lipped about everything. The legal question, then, is basically what rights to the beneficiaries have in such a situation to hold the trustee accountable? The Root Cause...

by Andy Chen | Jun 17, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

I was recently called for jury duty. For those of you wondering whether lawyers actually get called for jury duty, the answer is a most definite yes. I was ultimately not selected to be on the jury, but I did have to sit through two days of voir dire. Seeing it form the juror’s perspective was exciting given that I’m usually the one doing the voir dire in a setting like that. Anyway, the experience of having been through that gives rise to the topic of today’s post which is “What qualifications do you have to meet in California in order to be a juror?” Like with many things I go over on this blog, there’s an app for that… oops, sorry, what I actually meant to say was “There’s a statute for that.” In this case, the statute in question is Section 203 of the California Code of Civil Procedure, which states: “(a) All persons are eligible and qualified to be prospective trial jurors, except the following: (1) Persons who are not citizens of the United States. (2) Persons who are less than 18 years of age. (3) Persons who are not domiciliaries of the State of California, as determined pursuant to Article 2 (commencing with Section 2020) of Chapter 1 of Division 2 of the Elections Code. (4) Persons who are not residents of the jurisdiction wherein they are summoned to serve. (5) Persons who have been convicted of malfeasance in office and whose civil rights have not been restored. (6) Persons who are not possessed of sufficient knowledge of the English language, provided that no person shall be deemed incompetent solely because of...

by Andy Chen | Jun 15, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff, Torts

Today’s post is going to be another short one. In it, I’m going to go over the statute of limitations for a wrongful death lawsuit in California state court. As a reminder, a “statute of limitations” is the time period within which a plaintiff wanting to file a civil lawsuit (e.g. seeking money) must do it in. If the plaintiff waits too long (e.g. even by one day), they will lose their lawsuit simply because they waited too long. The topic of wrongful death litigation can get complicated when you look at questions such as (1) who is an acceptable plaintiff in a wrongful death suit?, and (2) what damages can be recovered in a wrongful death suit? I’ll go over these questions in future posts, but for today’s post, I’m going to look at just the time element involved, namely the statute of limitations the plaintiff has to file their civil suit within. In California, the answer is two years. Under Section 335.1 of California’s Code of Civil Procedure, a plaintiff in a wrongful death lawsuit must file that suit within two years of the date the death in question occurs. Section 335.1 itself says the following: “Within two years: An action for assault, battery, or injury to, or for the death of, an individual caused by the wrongful act or neglect of another.” Two years, however, is the general rule of thumb to remember. However, as with many things in law, exceptions can exist which may make the actual statute of limitations in your case shorter than two years. If that applies in your situation, you obviously...

by Andy Chen | Jun 13, 2021 | California, Statutes... and stuff

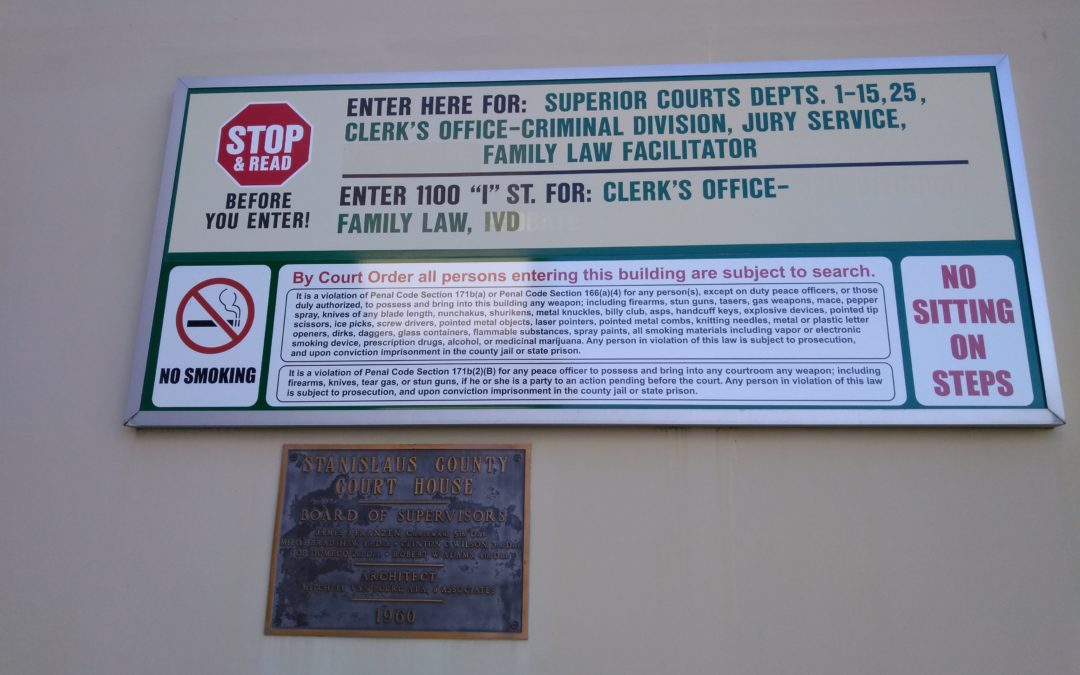

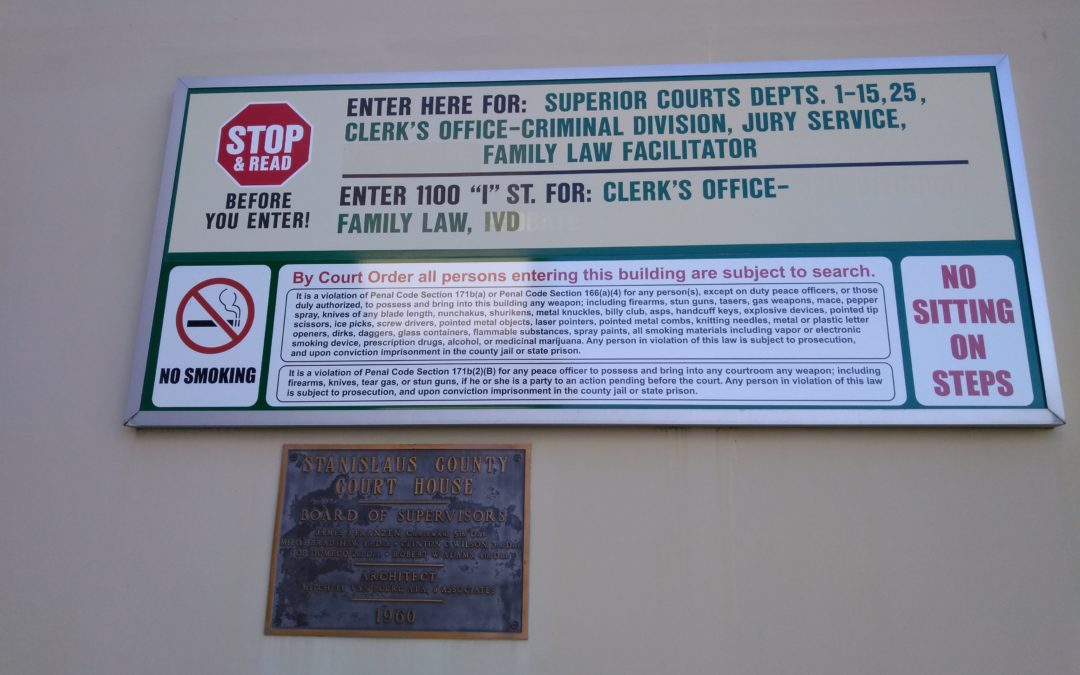

I would have thought it common sense that you shouldn’t bring a weapon to court unless you’re a law enforcement officer, using the weapon as evidence in a case, etc. However, in case it isn’t common sense, there’s this sign at the entrance to the Criminal and Family courthouse in Modesto, California. If you look under the red wording that says “By Court Order, all persons entering this building are subject to search”, you’ll see that it’s a crime to bring any of a whole littany of weapons in to the courthouse, including but not limited to, firearms, stun guns, tasers, gas weapons, and mace. The statutory authority for that is California Penal Code section 171b which, in a nutshell, outlaws the bringing and possessing of weapons in to a state or local public building. Section 171b also lists out a whole bunch of exceptions to this prohibition, such as law enforcement officers, people using the weapon as evidence in a case, and people who have been specifically granted permission to bring the weapon in. The prohibition does, however, remain in effect (i.e. it’s an exception to the exception to the prohibition) as to those persons who are parties to a case. For instance, a law enforcement officer can carry their firearm if they are on-duty (e.g. a sheriff’s deputy working as a baliff at the courthouse), but if they are showing up for a child custody hearing in their own divorce, then they can’t. You can read over the entirety of Section 171b at your leisure, but I want to point out the section’s definition of a “state...

by Andy Chen | Jun 12, 2021 | California, Criminal law, Law School Help

In today’s post, I’m going to go over the California crime of Identity Theft. In this series of posts that I’ve, apparently, labeled “Law School Help,” I’m going to try and go over terms (e.g. common criminal offenses) that ordinary people might have heard and provide a basic description of the legal authority (e.g. the particular statute section), the elements involved, and any sentence that the offense in question might carry. In prior posts, I’ve gone over questions like “What is Consideration?” and “What is a Common Carrier?” If you’re a law school student and you’re reading this, hopefully this series of posts provides you more real-world or practical knowledge compared to the more abstract or theoretical concepts you’re learning about in the classroom. Anyway, the topic today is the criminal offense of Identity Theft. Identity Theft is, unfortunately, extremely common. Some of you reading this have probably been the victims of it yourself. In California, Identity Theft is a crime and it’s covered under Section 530.5 of the California Penal Code. Section 530.5 goes over several different flavors of identity theft which I’ll go over in a moment, but the underlying offense of Identity Theft consists of: Willfully obtaining Personal Identifying information of another person Using that Personal Identifying information for any unlawful purpose. “Unlawful purpose” includes, but is not limited to, obtaining or attempting to obtain credit, goods, service, real property, or medical information This use of the Personal Identifying information is done without the consent of this other person. If you want to look it up, this is all in Section 530.5(a) of the California Penal...